Courage of Convictions: Esther and Peter by Jennifer Henry

Sermon delivered at First Christian Reformed Church in Toronto on the Book of Esther on September 27, 2015

In her commentary on this week’s lectionary Kathryn Schifferdecker suggests that preaching from the Book of Esther “is not for the faint hearted.” Maybe. But I can tell you that the other lectionary texts, which included “if your hand causes you to sin, cut if off,” (Mark 9:44), also provoked more than a little fear and trembling. So here we are, and, to be honest, I am more than a little drawn to this rare, named, female protagonist in her mythic story of hyperbole, with its twists and turns. If we had read the whole book, those of us who remember it from Sunday school will find that the teachers might have left a few parts out– parts that didn’t pass the censor board. Even if we read it as exaggerated drama, like a kind of passion play, certainly not a history, there are still some serious dilemmas. Chief among these is how justice converts to brutal vengeance when protection of an oppressed community exceeds any reasonable definition of self defense.2 I hope you will forgive that I have chosen to bracket that issue and focus in on other aspects. Dealing with the vengeance theme within scripture would take much more than one sermon. And before engaging with the story of Esther, I want to tell another story. This one is a little more recent and very real.

It was a very hot day this August, when a group of people gathered together in a cemetery in Ottawa. They were there to unveil a plaque and give tribute to a man whose name many would not recognize. Peter Henderson Bryce was born in Ontario in 1853.3 He became a doctor, one of the foremost experts on tuberculosis, a founder of the Canadian Public Health Association. At the age of 51, he was named the Chief Medical Officer of the “Indian” Department. It was in that role that he investigated 35 Indian residential schools on the Prairies and found that 24 percent of the children who had been at the schools had died; 75 percent at one school which had provided a full report. These were staggering numbers in comparison to the rest of the population. Claiming that “medical science knows just what to do” to stop the children from dying—tuberculosis exacerbated by malnutrition and neglect being the main cause–he made urgent pleas to the Government of Canada.4

His words were ignored and children continued to die. He went to the Ottawa Citizen, the Saturday Night Magazine, and ultimately told what he had found in a book called “The Story of a National Crime.” Along the way he successful engaged a few colleagues in his relentless pursuit of justice, such as noted human rights lawyer who said just as “Canada fails to obviate the preventable causes of death it brings itself into unpleasant nearness to manslaughter.”5 Bryce saw things within the big picture. For him Canada’s treatment of Indigenous peoples “…amounted to nothing less than an infuriating and criminal disregard for the treaty pledges.”6

He never gave up, but neither did the government, relieving him of his post, and actively undermining his reputation. Peter Henderson Bryce–a man with the courage of his convictions.

Let’s return now to the Book of Esther and remind ourselves of the plot since we got only a small slice this morning. Esther is a Jewish orphan living in the Diaspora, whose beauty, and a strange turn of events, makes her a Queen of Persia. The Book of Esther is about a plot to kill the Jews, hatched by Haman the notorious villain. Esther is convinced by her cousin Mordecai to find her courage and intercede with the king, for her people, to avert genocide. What follows are a series of reversals—Esther is welcomed and not condemned for her intercession, the villain is hung on gallows he built for Mordecai, and the Jews, rather than being annihilated, defend themselves, causing the massive death of their enemies. This is not historical biography, like the story of Bryce, but a more like a legend, perhaps to explain the origins of Purim. And yet I think there is some value in reading these stories, these characters, in tension with each other. When I did so three insights, three messages emerged.

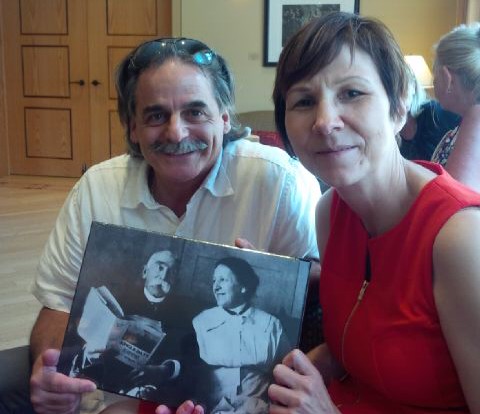

Valerie Galley

Valerie Galley Program Manager Ed Bianchi and KAIROS partner, Dr. Cindy Blackstock, hold a photograph of Peter Henderson Bryce and his wife at a gathering held to unveil a plaque in his honor. Photo by Valerie Galley

First, we must always look for those who can expand our moral view. I often hear folks talk about the Indian residential schools as a product of their time, a sense that we are unfairly applying hindsight in expecting a different treatment of Indigenous children at the time. “People back then didn’t know any better.” But what Bryce reminds me of is that in any historical situation of great wrong, there are always people, at the time, who have the moral vision to recognize the wrong for what it is. Someone who sees, someone who knows, and then someone else and then another, until there is a shift in our collective moral vision and slavery is not longer valid, violence against women is a sin, Indigenous peoples are nations, equal in dignity and rights, or nature has rights.

In the book of Esther, Mordecai is the one who sees, the one with moral vision, the one who recognizes that ”an innocent nation is being destroyed” (Esther 4:1, Gk). He is the one to expand Esther’s moral vision—challenging her to recognize the threat of genocide through her Jewish eyes, not those closed by her queenly privilege.

It is my contention that there are always those who know. And I would ask: who are those people for us now? 20 years ago, we might have named those who saw the potential climate change impact of our addiction to fossil fuels. Who are those with clarity, convicted by a moral truth that we continue to deny? Or to be said another way, poignant for our current reality, for what will our children and grandchildren be asked to apologize? We must always look for those who can expand our moral view.

Second, once we know, once we are convicted of a moral wrong, we must find our voice however futile it seems. Speaking out always matters. Mordecai challenges a fearful Esther not to keep quiet. We can hear her trepidation in a part of the text we didn’t read this morning. She says to Mordecai: “all nations of the empire know that if any man or woman goes to the king inside the inner court without being called, there is no escape for that person”(4:11). But despite her fear Mordecai compels her go to the king, unsummoned, by appealing to her solidarity to use her privilege for her people. Was it “…not for such a time as this that you were made queen” (4:14). Esther’s word sets in motion, somewhat circuitously and aided by coincdence, a series of dramatic reversals towards her peoples’ protection from their enemy. The story becomes an illustration, however mythically, of the power of a courageous voice.

Not surprisingly, when we return to the realism of Peter Henderson Bryce, we find a far more muted result. His persistent call found little or no resonance amongst the powers that were. He could not stop the dying. We now know that the odds of dying for children in the residential schools were greater than the odds of dying for Canadians serving in World War II. However, far past his time, his words, documented in research, in articles, begin to sink in, to contribute to shifts in policy, however small. And his words matter now. They echo through history to validate and affirm the truth of the survivors. His words affirm the families who knew something was terribly wrong. They honour those who never knew the truth of what happened to their children. His voice matters, now, to the process of reconciliation, and affirmation that there were, there can be, settler folk who will stand up. His words today weave trust, and build reconciliation.

It is my contention that our voices always matter. What voice must we utter now? Where are we, as people of faith, as churches, silent when we know we must cry out? Even if there is no observable impact in our time, on what must we speak so that our words echo through the ages until they find their place and time? When we observe injustice, we must find our voice. It always matters.

Finally, a last message, that community more than privilege can bring courage in the face of risk. Both the person of Peter Henderson Bryce and the character of Queen Esther are not without privileges. I identify with them, in different ways. My own commitments to solidarity with the excluded do not take away what Paulo Freire calls my “marks of origin”—white, settler, middle class. Bryce bore some similar marks. And yet, he faced some serious consequences; he was fired and his reputation disgraced. We must remember that it was nowhere near the risk faced by Indigenous parents who could be jailed for trying to protect their children. But, he was not shielded from risk. Standing up had consequences. I want to believe that those who stood with him, precious few, but some, including human rights lawyer S.H. Blake, helped sustain his courage.

In the story of Esther, it is clear that she was surprisingly spared. Her queenly privilege would not have necessarily protected her from the decision to speak truth to power. Despite that status, her standing up could very well have had dire consequences, including the loss of her life. For me, one of the most interesting parts of the story is that when she is afraid, when she is trying to summon her own courage to respond in solidarity, she asks that the Jews be gathered. And Esther, with her maids, and the broader Jewish community all fast for three days to give her the strength to meet the king, supporting her until she has the courage of her convictions.

If we choose to add our voice in solidarity, to speak truth to power, to name injustice, our privileges may cushion us, but they will not ultimately protect us. There may be consequences. Not as grave as those of our global partners—in Colombia or the Congo—where a word raised for human rights can mean their own death, but still possible unknown consequences.

In Canada right now, dissent, however principled, reasoned and constructive is not well tolerated by those in power. If we are faithful in naming injustice, if we respond to calls of solidarity, it is important to find our courage in one another. Churches acting together, aligning with others of faith and conscience, coming together in social movements, finding strength to say aloud that which is not easily said. Even if that is: “there is another, more caring, more just way.”

The oddest thing about the Hebrew narrative of Esther is that there is no mention of YHWH, no mention of God. She fasts, but does not pray. This troubled translators and scholars but I am undisturbed. To me the text is saturated in faith and hope. The Book of Esther, as a story, could be one illumination of the great saying by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” The story works out—well, in one way—genocide of the Jews is thwarted. And while we have the dilemma of vengeful violence, it is, through Jewish eyes, a story about reversals towards the saving of a marginalized people, the saving of God’s people. God acting, not obviously, but subtly as midwife, as facilitator of an unfolding justice.

And yet, in that bending arc, human action matters too. Mordecai’s moral vision and deep wisdom was essential. Esther had to find the courage of her convictions, and she needed the clarity of her cousin and the accompaniment of her people to do so. Whether or not she prayed, might she not have been lifted up by the faithfulness of others?

God’s dream of justice fulfilled ultimately matters. It is our consolation, our challenge and our hope. But so also do we matter. We are not absolved from just action, even from courageous action, by a faithful unfolding of God in history. Christ sought disciples—“I do not call you servants any longer, I call you friends”—to collaborate with him in bringing about God’s beloved community on earth. Our justice is what God requires.

Peter Henderson Bryce was a Christian, a Presbyterian. I have no doubt that God worked through him, that he was a flesh and blood, imperfect, but incarnate witness to God’s radical inclusion. A faithful voice against injustice. I wonder who stood with him in his church community, a congregation in a denomination that collaborated with government in running the schools. What if many had stood with him, engaged with him in the fast to loose the bonds of injustice? What if he had the solidarity and the collective moral voice of his whole denomination? What if? What if?

Peter Henderson Bryce, presente.

___________________

1 Schifferdecker, Kathryn M. “Commentary on Esther 7:1-6, 9-10; 9:20-22.” https://www.workingpreacher.org/preaching.aspx?commentary_id=2631. Accessed on September 25, 2015.

2 See Collins, John J. 2002. Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis: Augsberg Fortress Press, p.543.

3 This description of Bryce’s life was drawn from an excellent summary prepared by First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and included in the description of the award offered in his honour. http://www.fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/PETER%20HENDERSON%20BRYCE%20adult%20award%202015.pdf.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid

6 Green, Adam J. “Humanitarian, M.D.: Dr. Peter H. Bryce’s Contributions to Canadian Federal Native and Immigration Policy, 1904-1921.” MA Thesis. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk1/tape9/PQDD_0007/MQ42624.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2015, p.99.