Spirited Reflections on sheep and goats

The “sheep and goats” passage from Matthew: 25 is a familiar one to Christians who yearn for God’s justice in our world. I was recently asked to preach on this passage and decided to consider three different perspectives.

The first perspective is from my students at The King’s University in Edmonton, Alberta in a weekly drop-in Bible study I lead.

I was not surprised by their understanding of the text. They read this passage from a place of wondering what will separate those going to hell from those going to heaven. More specifically, they read it hearing the call to be people who feed the hungry, give water to the thirsty, hospitality to the stranger, clothe the naked, care for the sick, and visit the prisoner.

This is what God wants from them. And this is how they will be judged– sheep or goats.

More than that, the people they are supposed to care for, in their minds, is everyone and anyone who might need food, drink, care, or a visit. For them, this is a universal call to all people to care for all other people.

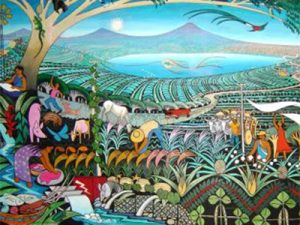

The second perspective comes from a group of people in Lake Nicaragua, Nicaragua half a century ago. During the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza a diverse group of gathered together weekly with their priest, Ernesto Cardenal, to discuss the weekly Gospel passage. Cardenal recorded their discussions in a book called, The Gospel in Solentiname:

“These discussions took place during the Somoza dictatorship; the dictatorship was always a part of them, along with the hope that liberation would soon come.”

Maybe it shouldn’t be surprising that this group reads this text very differently than those of us gathered at The King’s University in 2017!

One Solentiname group member says:

“One very important thing that I find in this Gospel is that it’s an announcement of the definitive triumph of love, of justice, of the new society, and the defeat of capitalism.”

Felipe says

“I see that when Christ speaks of the Last Judgment he doesn’t speak of religion, prayer, ritual: he spoke only of social needs.”

And Alejandro responds:

“Let’s make no mistake about that: there are religious people who think they are good people because they give aid, alms, old shoes. That’s not what Christ demands in this Gospel; it’s a total change in the social system.”

They go on to discuss, at great length how Jesus identifies with “the needy, the poor, the humble.” Or, as Alejandro puts it, “With everybody that’s screwed.”

My students read this passage from a place of power, hoping they can live up to the call.

Those in Solentiname read it from a place of relative vulnerability and even anger- longing for justice now.

To them, this story doesn’t bring anxiety or uncertainty, it elicits righteous anger and even hope that things might be set right…and that those among them, responsible for evil, will have to pay.

The third perspective is that of a theologian from within my denomination. Andrew Bandstra wrote an article on this text for the November, 1983 edition of The Banner (our denomination’s publication).

Bandstra describes how he came to change what he believes this parable is about. Formerly, he saw this passage much like the students in my Bible study did, as a universal call for Christians to care for all people. After much study, however, he changed his mind. The entire story, not only for him, but for most theologians who engage it, hinges on who you think the “All Nations” who are gathered before the King are in verse 32 and who you think the “Least of these brothers” are in verses 40 and 45.

Bandstra, disappointed, became convinced, mostly because of how Matthew uses these phrases at other times, that “All the nations” represented the nations to which the gospel would be brought and that the “least of these brothers” were meant to be understood as Jesus’ disciples who bring the message.

Bandstra concludes:

“On this understanding, the message of the parable is more appropriate for Mission Emphasis Week than for World Hunger Sunday; its message is more about the work of evangelism than about the diaconate; it is more about mission than about benevolence.”

All three of these settings read the text very differently, and I appreciate each perspective.

Interestingly, however, they are all concerned, in different ways, with questions of who will be proved righteous and who will have to pay.

Who will finally be the sheep and who will be the goats.

This makes it easy to approach this text as sort of a manual for getting into heaven.

…care for all of those around you who are in need.

…be on the side of the people…the side of the revolution.

…care for those sent in Jesus’ name.

But one thing I find interesting in this text is that both the righteous and the unrighteous are completely ignorant of what they have done. Their actions did not come because they were concerned with the question of their eternal destination.

The Lord praises the righteous for doing all these beautiful works and they don’t just accept it; they look around at each other and then, dumbfounded, ask,

“When did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink?

When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you?

When did we see you sick and in prison and go to visit you?”

Likewise, the goats ask the same questions… when did we see you in need and ignore you?

Neither the sheep nor the goats have any idea what they are doing. We may be prone to read this text as a “How-to” as far as getting into heaven is concerned. But maybe it is more of a description of the hearts of sheep and goats.

And I think…

It is too easy to read this text and see the poor, the vulnerable, the sick, the prisoners not as real people, but as pawns in a story that will determine the eternal destiny of everyone else. Did you love them or did you not?!

If anything separates the sheep and the goats in this story it seems to be that the sheep refuse to see the “needy” as only “players” or “things” in the story that will determine their own eternal destiny. In fact, that notion does not even cross their mind! They simply see friends—friends who deserve dignity. Friends who have something to offer. And friends who, yes, may need some care.

And notice that they do nothing extravagant. Their actions are small acts of kindness.

In the end, they don’t heal the sick; they simply care for a coughing friend when she is sick. They don’t solve the broken system that leads to mass homelessness; they give a sweater to a friend. They don’t rescue a prisoner or prove her innocence; they just visit a friend. They don’t solve world hunger; they share their table with friends.

In the end, it is not the calculating, spiritual temperature takers, who are so often comparing themselves to others—those whose every thought is about escaping the fires of hell, or of living in eternal paradise—who cared for the King along the way.

In fact, it is not even those who saw Jesus in their neighbor as they were caring for him. It is simply those who gave a bit of what they had to someone who needed it a little more than they did. And an ignorant lot it is, they had no idea what they were doing. But therein lies the beauty, they couldn’t even consider using the marginalized as a pawn in their own story. Their hearts are not wired that way.

In a way, the sheep have learned to be human. Or maybe not forgotten how to be human. And humans, made in the image of God, as we all are, care for one another.

As Oscar from Nicaragua says,

“The eternal fire, it seems to me, is the torture of selfishness.”

Those who are always trying to get ahead, who never have enough, who see others as competition or threats, or inferior, and not as friends.

And that is why reading this as a how-to manual for getting into the kingdom will always fall short…it is too self-focused.

And that is where we have to continue to look to Christ.

May Christ’s love and mercy and assurance give us peace.

And then, in being washed by that love and mercy, and looking to Jesus,

may our hearts continue to be human hearts and not goat hearts.

May we see others not as a means to an end, or as competition, or as inconsequential.

May we see others as friends…just as Jesus sees us as friends (John 15).

Tim Wood is Campus Minister at The King’s University in Edmonton, Alberta, Treaty 6 territory, and represents the Christian Reformed Church in North America on KAIROS’ Steering Committee.