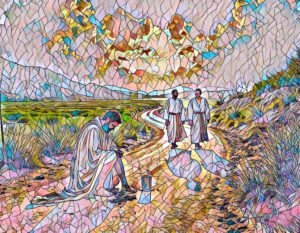

Who is my Neighbour?

Jubilee Preaching Aid for July 13

Readings for the Fifth Sunday after Pentecost (Year C)

- Amos 7:7-17

- Psalm 82

- Colossians 1:1-14

- Luke 10:25-37

In the introduction to the story of the Good Samaritan in the gospel of Luke, a lawyer asks Jesus, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” We often think about eternal life in terms of “the afterlife.” But, if eternal life is the fullness of our union with God, this narrative suggests that Jesus desires to set us on that path by teaching us how to be one-with-God here and now.

As it turns out, this path to union is rooted in a community that loves without boundaries. Love of God and neighbour are interwoven.

In the lead up to the story of the Good Samaritan, the lawyer wants a black and white verdict on what we must do to ensure our place with God; he is pursuing a precise ruling on “who is my neighbour?” By contrast, Jesus seeks to create an expansiveness in our heart and mind that will draw us more deeply into Love.

This space of expansiveness doesn’t call for legalistic distinctions, but rather a story.

Given the tensions between the Hebrews and Samaritans, it would have been jarring for the people listening to Jesus’ story to hear that a Samaritan was the hero of the story. It would have been equally jarring to hear how the characters who follow the purity rules (rules which basically served as guidelines for ensuring one’s holiness), break the connection between love of God and love of neighbour.

The religious leaders seem to think they’re putting love of God above all else. But, by crossing the road, they undermine both love of God and love of neighbour. Instead, it’s the Samaritan who lives from the place of interconnected love. The Samaritan alone enters the expansiveness of this space.

We tend to hear this story from a place of all-knowing. We’ve already decided what it means to us. We know all about the Christian call to charity and direct service. But what if the transformative challenge in the story is less the generosity of our charity and more the refusal to put boundaries on whom we see as our neighbour? What if the transformation lies in how the loss of boundaries creates a new sense of right relationship within and between communities, and a new sense of who owes what to whom? Is this where our oneness with God finds new depths?

The disconcerting question of “who owes what to whom” is also at the heart of the Jubilee 2025 campaign to cancel the unjust debts owed by debt-distressed countries. Many people like to see it as a matter of charity, emphasizing simply that the debts of many developing countries have become unsustainable, and debt payments are taking funds from badly needed investments in education, healthcare and climate action.

However, when Pope Francis announced the Jubilee year, he framed debt cancellation as a matter of justice, not charity. He did so by spotlighting the interconnections between the global crises of ecological debt and financial debt.

The term “ecological debt” refers to the environmental damage in the Global South caused by the production and consumption patterns of nations in the Global North. Through this lens, countries of the Global North are seen as delinquent debtors and countries of the Global South as long-owed creditors.

Climate debt is one part of the concept of ecological debt. It highlights that industrialized countries are the ones most responsible for the vast majority of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, while the countries who will bear the worst impacts of climate change are those least responsible. The concept of climate debt insists that the countries that contributed the most to climate change must take on a fair share of the cost, so that countries most vulnerable to climate change are better able to mitigate and adapt to the threats.

Who is my neighbour? If, like the Good Samaritan, we respond to that question with an appreciation for the hidden communion at the core of life, we may find ourselves experiencing a taste of eternal life in the here and now. Will we not also find ourselves seeking justice by weaving together actions to address both ecological and financial debt?

Sue Wilson is a Sister of St. Joseph. She is Executive Director of the Office for Systemic Justice and serves on two committees for the Jubilee Debt Cancellation campaign — theology and advocacy.