Good Things Can Come to Those Who Wait—and Weep by Stephen Bede Scharper

Stephen Bede Scharper, Roman Catholic, is a former editor with Orbis Books and Novalis Publishing, and currently associate professor of environment and religious studies at the University of Toronto.

If good things come to those who wait, they also can come to those who weep.

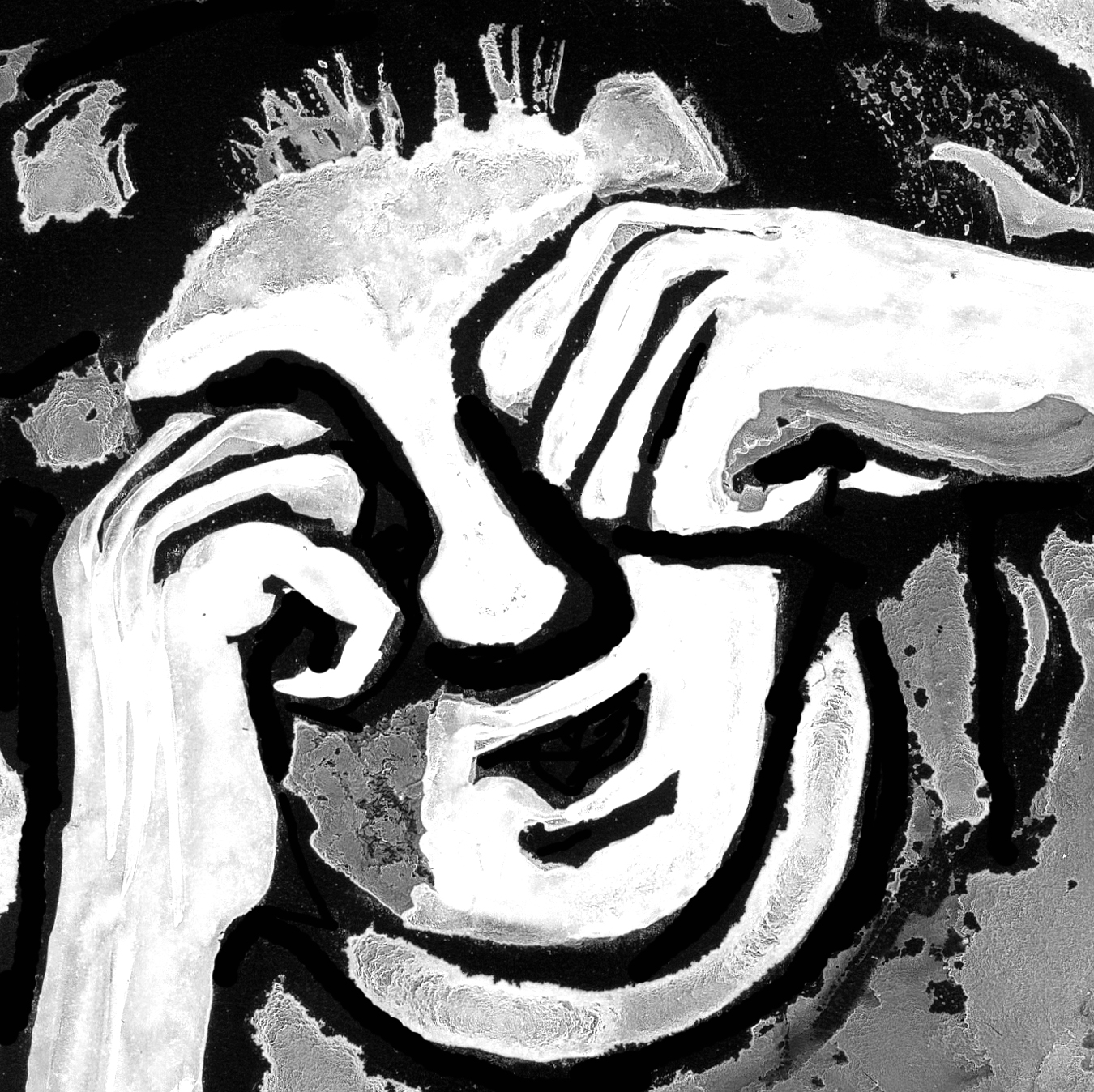

In John’s Gospel, Mary Magdalene stays at the empty tomb and weeps.

She is rewarded by an encounter with the Risen Christ.

A former prostitute, a scorned woman among a scorned gender, Mary is the first “Easter” person. If it were not for Mary, chances are there would never have been an “Easter people.”

After rising early and venturing in the dark to Jesus’ tomb, Mary discovers that the stone sealing the tomb has been rolled away. It seems that Mary had a sense, more than the other disciples, that something remarkable was a foot at the tomb, the apparent end-of-story of Jesus’ whirlwind, breathtaking, miracle-laden time among them.

And she also had the courage to be present to the body of Jesus, soon to be the Body of Christ, when others in the movement, including Peter, had denied ever knowing him as a man, let alone as a corpse.

Mary sprints from the scene to convey the extraordinary news of the empty tomb to Simon Peter and “the other disciple, the one Jesus loved.”

After racing to the scene and viewing the vacant chamber, Peter and the beloved disciple do a curious thing. Though they “believed,” they take their belief to their homes. Perhaps they were fearful of the Roman guard, who may have been watching the tomb to ensnare other conspirators in the Jesus movement. Perhaps they wanted to process this all in private, to hide their feelings, and, if flowing, their tears.

But Mary sticks. And cries. Openly. She bears witness to her grief “outside the tomb.” But something compels her to bend over and peer into the tomb. It is in that moment of bending over, and gazing through tears of sadness and confusion, that the joy, wonder, and truth of Easter are born.

Seeing two angels in white, and then spying an apparent gardener, Mary asks where Jesus’ body has been laid, and she states she “will take him away.” She remains, despite all that has transpired, the steadfast custodian of the crucified Jesus.

And she only recognizes Jesus when he speaks her name. Well before Pentecost, Mary is directed by Jesus at the tomb to proclaim his impending ascension to “my God and your God.”

While Peter may be the rock upon which Jesus built his Church, Mary is the cornerstone of the Easter narrative, a stone rolled away from apostolic recognition and at times tossed onto a patriarchal rock pile of marginality.

And yet, she is blessed, like all who mourn. In her unabashed grief, in her intrepid sorrow, she becomes the first human proclaimer of the Paschal mystery. Mary reminds us that certain stones, like certain persons, who are tossed or rolled away from historical fame or celebrity spotlights often become the cornerstones of lasting and beautiful realities.

She reminds us that it is not only when we let our light shine, but also when we let our grief and love be known and shown, that wondrous things can happen—like Easter.