Learning from historical trauma at Yad Vashem

By Lori Ransom

For most of the past 15 years, my work has focused on healing and reconciliation from the historical trauma suffered by Indigenous children in Canadian residential schools. This has led to a deep interest in how communities deal with subjects such as commemoration, memorialization, trauma (including intergenerational trauma), racism, genocide and its legacy, the quest for truth, healing, and reconciliation, and how historical trauma affects relationships at individual, family, community, national and international levels. On my trip to Israel/Palestine, I was mindful of time I had spent working with members of the Jewish community in Canada to bring together survivors and intergenerational survivors of the Holocaust and of residential schools for a dialogue. This event proved to be remarkable in illuminating commonalities in the human experience of dealing with racism, trauma, and genocide.

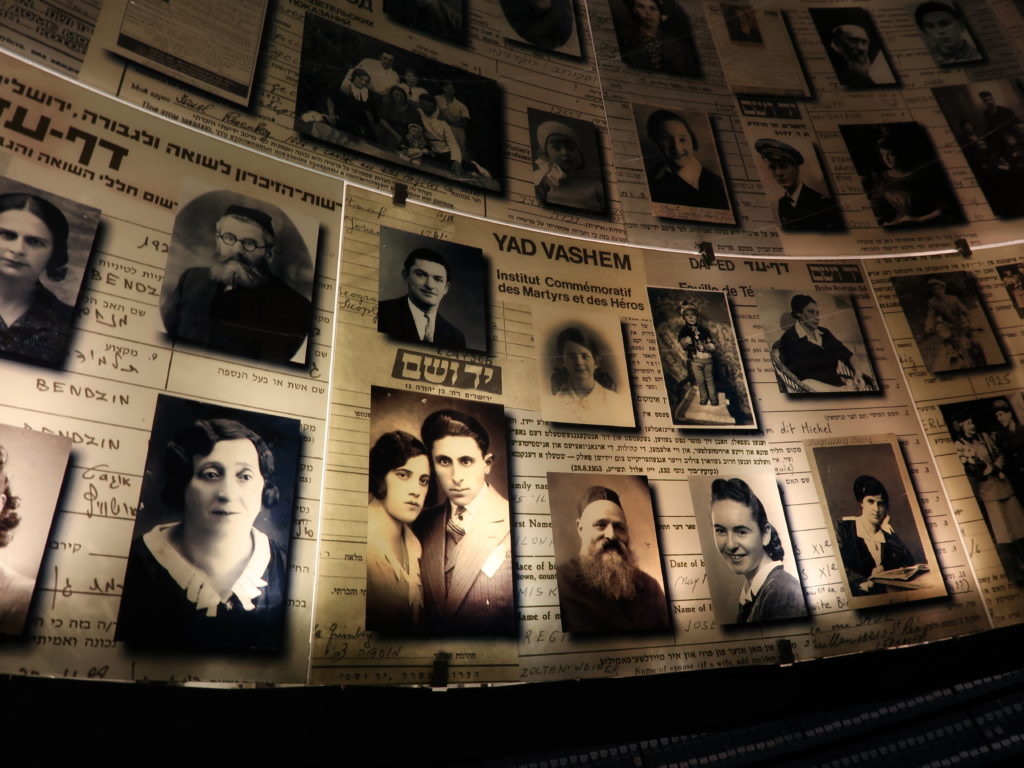

So I arrived at Yad Vashem—the Holocaust Remembrance Centre in Jerusalem—with a deeply held sense of the importance of the visit. Emotionally I braced myself for a similar reaction to that I had felt in Berlin in 2015, upon visiting the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, and its powerful exhibits that stirred up tears and emotions felt long after the actual visit.

Our group concentrated its time on an exploration of the Holocaust History Museum—one of several facilities and spaces at the 50 acre site. The museum’s architecture—designed by Israeli-Canadian Moshe Safdie–is striking and charged with symbolism. The audio guide I was provided with described it as evoking the idea of a saw cutting the hill from side-to-side, meant to symbolize the permanent scarring of the Holocaust on the Jewish people and all humanity.

While the overall story of the Holocaust presented in the museum was familiar to me, the level of detail in information panels and the large number and variety of artifacts revealed some new historical facts and poignant stories. For instance, a pair of fragile, coppery, wire rim glasses were displayed. They had belonged to a mother who had been sent to the gas chamber directly upon arrival at a concentration camp (Auschwitz if my memory serves correctly). Her daughter, who had been selected to work in the camp, had entered a disrobing area not long after her mother and had seen her mother’s coat on a hanger. The daughter took the glasses out of a pocket of her mother’s coat and secreted them on her person until she was liberated from the camp at the end of the war. This is a deeply personal example of the importance of memorialization; of how everyday objects can carry the story of a life and a precious relationship.

I was also struck by the amount of poetry, diaries, and other written reflections that have survived to be preserved at the museum, including, most surprisingly, messages to loved ones written on tiny pieces of paper by people as they were transported to the camps by train. One can imagine how they must have felt as they slipped these tiny messages through the cracks of the boxcars in which they were travelling —a mixture of doubtfulness, desperation, and hope— that these messages would ever be found. And so it is all the more astonishing that so many have been found.

Yad Vashem is beautifully situated on a hill overlooking Jerusalem. The natural beauty of the site was apparent on what turned into a beautifully sunny day. It is lovingly and reverently maintained.

In Canada, we are only just beginning to memorialize and tell the story of residential schools in museums and other interpretive centres. I look forward to the creation of both national and regional commemorative and educational sites such as Yad Vashem. We are also only just beginning to understand the effects of historical trauma on individuals, families, and communities. I was curious, and remain curious, to hear Jewish perspectives on the impacts of the Holocaust intergenerationally.

Rabbi Jeremy Milgrom met with us immediately following our visit. He said that from his perspective, Israelis do not feel that their trauma has ended. In other words, it is hard for them as a people to move forward and heal when a sense of ongoing trauma prevails. He added, “Not only does the unresolved conflict not foster healing from the trauma, various actors exploit and manipulate our vulnerability and use this deep insecurity to preach against making peace. Making peace demands trust, but we are taught to believe that the world hates us. We must never let down our guard. We are a garrison state.”

As a member of a group seeking to understand and support the work of those working for justice and right relationships in Israel and Palestine, I found this response to be tremendously helpful. While my direct experience of Israel/Palestine is limited to a 10-day trip, my experience of the legacy of historical trauma in Canada leads me to wonder about the need for healing among the people of Israel. Milgrom noted that “the Holocaust and the state of Israel are inseparable.” I am led to wonder about the specific ways in which the experience of the Holocaust, the resulting intergenerational trauma, and of the world’s complicity in not doing more before, during and after the Holocaust to protect, support, and welcome Jewish people into our nations have shaped national identity in Israel and the way the state relates to the world and to its neighbours.

The deeply troubling state policies in relation to Palestinian people which we learned about on the trip seem at their core to be borne out of fear and, most troublingly, perpetuate inhumane treatment of the other, including children. They erect barriers, physical and otherwise, that seem designed to prevent relationship building and reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians. The tears of the present situation pile on top of the tears of remembering the horrors of the Holocaust. From what, from where, and from whom will the spark of healing come that will heal all of these many wounds?

Sadly, I learned after our visit that Palestinians are conflicted about visiting Yad Vashem. They are not conflicted about visiting Holocaust museums and memorials and do so outside the country. But they remember that three Palestinian villages were destroyed in 1947 at what is now the Yad Vashem site. Among these is Deir Yassim, the site of what is regarded the worst massacre of Palestinians in 1948; only nine members of the village survived. Hence, visiting Yad Vashem cannot be separated from their memories of what happened to Palestinians on that very land.

One might imagine that an element of healing in the Holy Land will be the creation of another site of commemoration and excellence in historical research and education: this one focused on the experiences of the Palestinian people, where Israelis, Palestinians, and other peoples from all over the world could come to remember and to learn, as they will continue to come to remember and learn at Yad Vashem, on the journey towards a better world for all of us.