KAIROS Interviews La Suerte (Sofía Acosta)

(sigue el texto en español)

Sofía Acosta Varea aka La Suerte is an Ecuadorian visual artist who designed Mother Earth and Resource Extraction: Women Defending Land and Water’s (MERE Hub) logo and has created all of the illustrations for KAIROS’ digital hub on the gendered impacts of resource extraction. This weekend on June 21, National Indigenous Peoples Day, KAIROS launches MERE Hub, the Canadian phase.

In this interview with KAIROS, Sofía discusses her work as politico-aesthetic demands for gender and ecological justice and Indigenous rights.

The interview has been edited for clarity. The original interview in Spanish is below.

KAIROS: Could you please interview yourself.

Sofía Acosta Varea: I am Sofía Acosta Varea, an Ecuadorian visual artist. My work encompasses an interdisciplinary practice that ranges from installation—through the intervention of photographs, archives, maps and testimonies—and ends with the use of graphics and murals. My work is an aesthetic-political commitment that, on the one hand, questions established gender narratives and, on the other hand, explores an art proposal that is post-extractivist, putting into debate contemporary notions of territory.

I have participated in several solo and group exhibitions in different independent galleries, inside and outside Ecuador. Among others, they include: Paisaje/Territorio Imaginarios de la selva en las artes visuales (Imaginary Landscape / Territory of the Jungle in the Visual Arts), which was curated by Ana Rosa Valdéz at MAAC in Guayaquil, Ecuador (2019), IDD Indicios de Data (IDD Data Indices) curated by Juan Carlos León in Quito, Ecuador (2019), Amazon Color in Seoul, South Korea (2014), and Esencial (Essential), a solo exhibition at El Conteiner in Quito, Ecuador (2017).

I was curator for the group show Ordinaria (Ordinary) at Arte Actual FLACSO (2018). The show sought those interactions that have not been legitimized because they have been considered domestic, feminine, or ordinary. I participated as an exhibitor and workshop facilitator at the Guadalajara International Book Fair (2015). Likewise, I spoke at a Human Rights and Arts workshop at Harvard University (2018). I illustrate independent publications, such as Decapitado (Decapitated, 2016) and Retratos del encierro (Portraits of Confinement, 2017).

Together with Adrián Balseca, we created the project Mirador: Visiones sobre el extractivismo (Mirador: Visions on Extractivism, 2019). This is a book that consists of an investigation into the different visual memories of peasant and Indigenous leaders who have been criminalized since the arrival of the Ecuador’s 6 mega-mining projects.

KAIROS: Much of your work focuses on mining. Why?

Sofía Acosta Varea: My work is founded on a critical attitude towards power, questioning all forms of violence that are inherent in it and that, perversely, have been assumed as normal. On the one hand, I question the power that is exercised over women, thus putting forth art that is self-referential or autobiographical; on the other hand, I confront state power and the violent imposition of extractive agendas in peasant and Indigenous territories of Ecuador.

At the initial facet of my work, I place my experiences at the axis of micropolitical exploration. Based on Rosa Martínez’s idea that “intimacy is political” and from a feminist standpoint, I approach self-referential aspects; I think of myself as a Latina woman who deconstructs identity processes typical of a conservative society.

On the other hand, I address the social and political problems that extractivist agendas provoke in the territories and in the subjectivities of people. My work is based on the different visual memories of peasant and Indigenous leaders. Through judicial files, testimonies, personal records, photographs of the communities, and maps, I outline a sociopolitical scenario.

My work is always accompanied by questions about the patriarchal and colonial political situation that we live in Latin America. Carolina Caycedo’s thinking constantly resonates with me: “I feel that artists are not on the frontlines of various struggles, but we can be immediately behind, helping to sustain those front lines, sustaining the thinking and spirit of those who are putting their bodies on the line.”

KAIROS: Could you speak about the illustrations that you created for MERE Hub Canada.

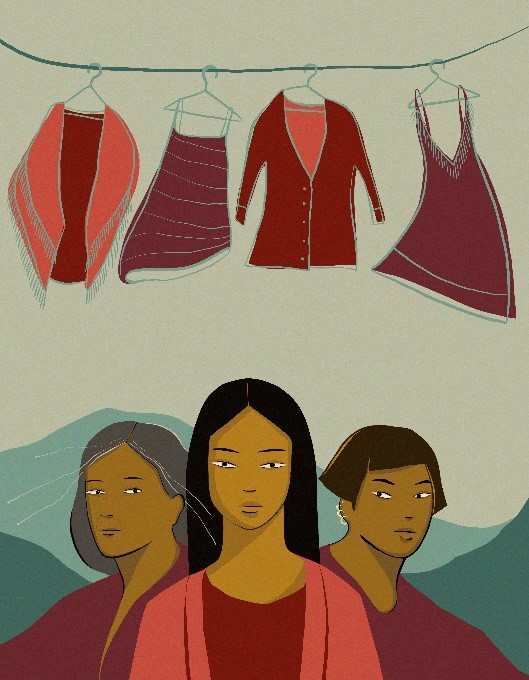

Sofía Acosta Varea: The illustrations I made for KAIROS focus on Canada’s extractive policies. The first illustration portrays three women land and water defenders, women from different generations and territories. The three share the same fight and are defending their territories in the foreground. They look straight ahead, with a fixed and resistant gaze. Behind them we see hanging red dresses, which represent and signify the absence of murdered and disappeared Indigenous women.

The second illustration talks about how Canada’s extractive policies extend beyond its own country. Canada is represented as this ambitious and greedy ‘being’ who is unable to be satisfied. He continues to apply his extractive agendas throughout the hemisphere.

KAIROS: What’s next for you? What are you working on?

Sofía Acosta Varea: For a year now, I have been researching my family’s photo albums. At first, I was interested in working with these archives because of the political and social burden they have within a specific historical context. However, while going through these photos, I met Elena. She is a woman, whose face has been scraped or erased from the photographs. When I began to sort the images, my fascination was to find out why this aggressive gesture was done. Even if not seeing her face intrigues me, I am now more interested in two other aspects of the investigation.

On the one hand, beyond her scratched-out face, I care about the context of where she is, who she is with, who photographs her. I am interested in investigating how the small family events that these images capture can build other discourses in the present. I am also interested in rescuing what remains of the faceless image—the materiality of the paper, the fungi of the photograph, the notes on the back, understanding how the passage of time and the humidity that invades the image already tell their own story.

This project, and its two possible inquiries, inscribe the artistic practice as an archaeological practice. As Akram Zaatari mentions: “The expansive work on photography and collecting takes an archaeological perspective: it digs into the past, brings out new narratives, and situates them in contemporary times.” It is these new narratives that emerge from photography as an object that catch my attention. I keep thinking about the possible formats to show or crystallize this work, because, for now, I sort and organize the images over and over again.

Sofía Acosta Varea (La Suerte) es una artista visual ecuatoriana quien diseño el logotipo de Madre Tierra ante el Extractivismo: Mujeres defendiendo el medio ambiente (la plataforma MERE) y quien también ha creado todas las ilustraciones asociadas con esta plataforma digital acerca los impactos diferenciados del extractivismo de KAIROS. Este fin de semana en el Dia Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (Canadá) KAIROS lanzara la fase canadiense de la plataforma.

En esta entrevista Sofía discute sus propuestas artísticas como demandas aestico-politicas por la justicia de género, la justica ecológica, y por los derechos para los pueblos Indígenas.

La entrevista ha sido editada para mayor claridad.

KAIROS: Te puedes presentar por favor

Sofía Acosta Varea: Soy Sofía Acosta Varea, artista visual ecuatoriana. Mi obra abarca una práctica interdisciplinaria que va desde la instalación, pasando por la intervención de fotografías, archivos, cartografías y testimonios, termina con el uso de la gráfica y el mural. Mi trabajo es una apuesta estético-política que por un lado cuestiona a las narrativas establecidas de género y, por otro lado, explora una propuesta de arte posextractivista, poniendo en debate las nociones de territorio contemporáneas.

He participado en varias exhibiciones individuales y colectivas en distintas galerías independientes dentro y fuera del Ecuador. Entre las que destaco: `Paisaje/Territorio Imaginarios de la selva en las artes visuales’, curaduría Ana Rosa Valdéz, MAAC – Guayaquil (2019), ‘IDD Indicios de Data’, curaduría Juan Carlos León, Quito (2019), ‘Amazon Color’, Seúl – Corea (2014), y ‘Esencial’, muestra individual, El Conteiner – Quito (2017).

Fui curadora en Ordinaria, muestra colectiva que buscaba aquellas interacciones que no han sido legitimadas por ser consideradas domésticas, femeninas u ordinarias, Arte Actual FLACSO (2018). Participé como expositora y tallerista en la Feria Internacional del Libro de Guadalajara (2015). Asimismo, participé como tallerista en Human Rights and Arts, workshop, Harvard University (2018). Ilustró publicaciones independientes como Decapitado (2016) y Retratos del encierro. (2017).

Junto con Adrián Balseca, realizamos el proyecto “Mirador: visiones sobre el extractivismo” (2019). Una publicación que consiste en una investigación sobre las distintas memorias visuales de los y las dirigentes campesinos e indígenas que han sido criminalizados desde la entrada de los 6 proyectos mega mineros del Ecuador.

KAIROS: Mucho de tu trabajo artístico se enfoca en la minería. ¿Por qué?

Sofía Acosta Varea: Mi trabajo parte de una actitud crítica al poder, cuestionando todas las formas de violencia que le son inherentes y que, perversamente, han sido asumidas como normales. Por un lado, cuestiono al poder que se ejerce sobre las decisiones y cuerpos de las mujeres, planteando así obras que surgen desde propuestas autorreferenciales o autobiográficas. Por otro lado, confronto al poder estatal y la imposición violenta de agendas extractivas en territorios campesinos e indígenas del Ecuador.

En la primera arista de mi obra coloco mi experiencia como eje de exploración micropolítica. Basándome en la idea de que “la intimidad es política” planteada por Rosa Martínez y desde una postura feminista abordo aspectos autorreferenciales, pensándome como mujer latina, para deconstruir procesos de identidad propios de una sociedad conservadora.

Por otro lado, abordo las problemáticas sociales y políticas que las agendas extractivistas provocan en los territorios y en las subjetividades de la gente. Trabajo sobre las distintas memorias visuales de dirigentes campesinos e indígenas. A través de archivos judiciales, testimonios, registros personales, fotografías de las comunidades, cartografías esbozo un escenario sociopolítico.

Mi obra está siempre acompañada de cuestionamientos a la coyuntura política patriarcal y colonialista en la que vivimos en América Latina. Donde constantemente me resuenan los planteamientos de Carolina Caycedo: “Siento que los artistas no estamos en la línea de frente de diversas luchas, pero si podemos estar inmediatamente detrás, ayudando a sostener esa línea de frente, sustentando el pensamiento y el espíritu de aquellos que sí están exponiendo sus cuerpos.”

KAIROS: ¿Podrías hablar de las ilustraciones que creaste para la fase canadiense de la Plataforma MERE de KAIROS?

Sofía Acosta Varea: Las ilustraciones que realicé para Kairos estaban enfocadas en la coyuntura de las políticas extractivas de Canadá. La primera ilustración retrata a tres mujeres defensoras del agua y la tierra, mujeres de diferentes generaciones y territorios. Las tres comparten la misma lucha y están defendiendo sus territorios en un primer plano. Ellas miran al frente, con una mirada fija y de resistencia. Atrás de ellas vemos vestidos rojos colgados, los cuales representan y significan la ausencia de mujeres indígenas asesinadas y desaparecidas.

La segunda ilustración habla de cómo las políticas extractivas de Canadá se extienden más allá de su propio país. Canadá es representado como este ‘ser’ ambicioso y codicioso, que no se satisface. Él cual sigue ampliando sus agendas extractivas en todo el hemisferio.

KAIROS: What’s next for you? What are you working on?

Sofía Acosta Varea: Desde hace un año, investigo los álbumes fotográficos de mi familia. En un principio me interesaba trabajar con estos archivos por la carga política y social que tenían dentro de un contexto histórico específico. Sin embargo, en la clasificación de imágenes me encontré con Elena. Ella es una mujer, cuya cara ha sido raspada o borrada de las fotografías. Al comenzar a las imágenes mi fascinación estaba en encontrar el por qué de este gesto agresivo. Si bien el no ver su rostro me intriga, ahora me interesan más otros dos aspectos para la investigación.

Por un lado, más allá de su rostro arañado de las imágenes, me importa el contexto de dónde está, con quién está, quien fotografía. Me interesa indagar en como los pequeños eventos familiares que presentan estás imágenes pueden construir otros discursos en el presente. Me interesa también rescatar lo que queda de la imagen sin rostro, la materialidad del papel, los hongos de la fotografía, las anotaciones al reverso, el entender como el paso del tiempo y la humedad que invade la imagen ya cuentan su propia historia.

Este proyecto y sus dos posibles indagaciones inscriben la practica artística en una práctica arqueológica. Cómo menciona Akram Zaatari: “El expansivo trabajo sobre fotografías y coleccionismo adopta una perspectiva arqueológica: excava en el pasado, hace aflorar nuevas narrativas y las resitúa en la contemporaneidad.” Son estas nuevas narrativas que surgen de la fotografía como un objeto las que me llaman la atención. Sigo pensando en los posibles formatos para mostrar o cristalizar esta obra, pues, por ahora, clasifico, separo y organizo las imágenes una y otra vez.